I was very excited to venture into the famous, greatly anticipated Shanghai Biennial. My first impression of the Biennial was that it was extremely user friendly. The signs were all written in both Chinese and English and the maps were as well. The description along the wall of the theme of “Translocalmotion” was very thorough and a good summary of the entire exhibition. I really enjoyed the layout of the museum and the common theme within each floor. It made viewing the artworks very accessible. One thing I did not like however, was within each floor themselves it was a tad difficult to locate certain pieces of work. For example, most of my artists were located on the 3rd floor. When I arrived however, the numbers on the map and the numbers physically located on the pieces of work did not correspond. It made things confusing if not a little irritating for my group and I.

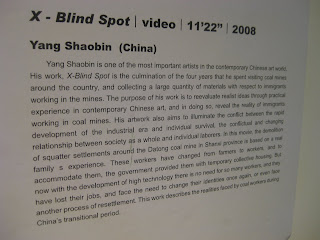

My group mates, Velvet, Sally and I walked into our first artist’s exhibit, Yang Shao Bin’s “X- Blind Spot,” shadowing the life of a coal miner in Datong, Shanxi Province. The four walls of the room were plastered with gigantic screens each showing an aspect of the coal mining life. The focus of each screen was not very clear; in fact the images were fuzzy and it added to the dirty and grimy feeling that the artist seemed to be going for. A bout of weariness washed over me and as I closed my eyes and just listened, I could easily imagine myself amidst the workers on their daily grind. On one screen were the pained and lethargic faces of the coal miners. I easily saw these miners as migrant workers, moving from their rural lifestyle of farming to the dangerous lifestyle of a coal miner. I could imagine these men leaving their families behind in an effort to be ale to support them later on, not realizing that if anything had happened to them their families would have no other source of income. Another screen showed the abundance of black smoke and/or pollution in the area. Another showed the strenuous, back breaking work of the life of a coal miner. The last screen displayed the medical difficulties of a coal miner, from x-rays to medicines to IV drips. The plaque introducing Yang’s work stated he sought to “reveal the reality of immigrants working in coal mines,” as well as “illuminate the conflict between the rapid development of the industrial era and individual survival, the conflictual and changing relationship between society as a whole and individual laborers.” Society as a whole pulled these workers to the mines to meet the demand needed of workers and the individuals pushed themselves to the mines to seek a better life. The layout of the 4 screens I believe added tremendous depth to the subject at hand.

The group of work entitled “Immigration” by Liu Ming really struck home with me. Her works were all brightly lit, and composed of tiny dots that made up the bigger picture. I thought the colors truly represented the Asian superstition of the power of the color of red to bring good fortune. It truly portrayed decadent nature of Chinese shrines. I believe she chose to create her paintings with a plethora of dots to symbolize the coming together of the lives of these immigrants when they leave their place in search of something better. The pictures of the Buddha shrines and sticks of incense reminded me of my family, all of whom have that makeshift shrine in their homes. Their religion was the one thing they could keep while they had to leave everything else behind. One work that interested me the most was “Immigration 004”---the one of the shrine in the grocery store. It seemed as if immigration itself was commonplace among all the necessities of Chinese life of flour and pepper paste. I believe that it went perfectly hand in hand with the theme of the exhibit: Translocation in Motion. It was a fusion of modernization while preserving traditions. I envisioned the story of a family leaving their hometown to open a grocery store in their new life. As a token of their past, they set up a shrine to pray for good health and well-being as they begin their new life in a new place. The shine represented the owner’s desire to preserve a part of them as their everyday life changes. It seemed as though these shrines were one stable part of the tumultuous cultural changes they were experiencing on the outside. The freshly lit incense signaled that the incense was changed daily, and thus served as a daily reminder of their values. I associated that with the incense that is lit daily in my home whenever my mother would pray to the gods for a healthy life and protection. I am almost positive that when the immigrants prayed to these gods it was for the same principles—their strive towards a healthy live and protection which was probably the catalyst for why they immigrated in the first place. Thus the shrines truly did serve as the cultural identity for many of these Chinese immigrants.

My favorite pieces of art were the works by Yu Hua and her conceptualization of cities. She paints rail lines—which represent the migration from rural to urban cities—and rollercoasters throughout colorful buildings. She dots her works with little animals who look like clones. Her paintings as a whole are painted with pastel colors and look like something that would appeal to children. Her paintings seem simple from afar but it is not until one moves closer to the paintings when they realize the amount of detail found inside. Upon closer observation for instance, I noticed the angry looks on the faces of the people in the paintings. The people in the painting all look the same, completely identical up to the slant of their beady red eyes. The people, who resemble bunnies, are dotted throughout the piece. I believe they represent the migrants who have settled into the urban sector. They slowly lose their own identity as they assimilate into the urban life. Their daily life consists of the same routine, working to make a living and returning home to the farmlands. Therefore they seem motionless, as if it was not even worth an effort to make a move. Contrastingly, there are also black ants dotted throughout the pieces, especially on the rail lines. These ants seem to be constantly in motion and I believe they represent the migrant workers who have just begun their journey to seek a better life. They are constantly moving because they are still awaiting the opportunity for them to assimilate. The ants seem to only be concentrated in one area of the rails however, as if something is deterring them from going any further. Perhaps the hukou, or household registrations, which tie each person to their places of origin, are holding the migrants back from reaching their desired destination. In one of her pieces there is a gigantic eye protruding from a telescope which I think represents the government’s role in all of these migrant displacement. The government is keeping a strict eye on the migrant movement. They are closely regulating what is happening in terms of the gap between urban and rural and are doing whatever is in their power to stay in control. These hints of control are apparent in most of Yu’s paintings as represented by whips or leashes. Inside these leashes are golden ducks which seem to be to signify the golden opportunity—what all the migrant workers are searching for. These ducks are controlled by bunnies that look different from the others, they are bigger and actually have distinguishable faces and features. It seems as though the desired ducks are unattainable and out of reach.

No comments:

Post a Comment